Flawed: Safe Playgrounds

How Safe Play is Harming Kids

A playground, in all its plastic glory and fanfare, is an essential part of a young child’s life. The slides, monkey bars, jungle gyms and other play structures provide entertainment and activity for a broad range of ages. In fact, playgrounds are one of the few unifying aspects among all childhoods. Everyone can think back to their favorite playground as a child and a game they used to play, and everyone can think back to an injury they got there too. So if playgrounds are so important, why are architects designing them to harm children?

As an adolescent, one thing must happen to ensure that a child grows up to be healthy: physical activity. The correlation is simple; if physical activity is present in the developmental stage of youth, an active lifestyle is extremely more likely to occur in adulthood (Telema 2009). These lifestyle habits that develop in the early years of life persist into adulthood and ultimately affect the majority of decisions made on a day to day basis (Rauner 2015). For example, the way a child frequently shares toys will dictate how they treat their personal items in an office space. Although simple and seemingly meaningless, these early choices have long lasting effects.

A playground provides a space for all of these healthy habits to develop. They encourage physical activity through play and positive social interaction through games. Clearly, playgrounds are important. But as lawsuits pile up and playgrounds are forced to change, they get worse. In the last 15 years, the open spaces have shrunk, the monkey bars lowered and the sand and mulch replaced by rubber. These changes do make the playgrounds themselves ‘safe’, but they sacrifice something incredibly important to get there: controlled risk.

Controlled risk is exactly what is sounds like; the ability to take chances without full consequences. It’s an especially important aspect of a playground. It teaches kids that this happens when I do that. In fact, a simple fall from the monkey bars can teach a child about the proper precautions to take with heights, and give them a warning story they won’t forget.

Controlled risk is exactly what is sounds like; the ability to take chances without full consequences. It’s an especially important aspect of a playground. It teaches kids that this happens when I do that. In fact, a simple fall from the monkey bars can teach a child about the proper precautions to take with heights, and give them a warning story they won’t forget.

By taking away controlled risk for guaranteed safety, a key aspect to the development of consequential thinking is forfeited. Children are growing up without learning about the likely danger in the world around them, and it shows. Over the last 15 years, a fear of heights in early teenagers has dramatically increased, and while the safety proofing of playgrounds may not be the only cause, researchers list it as a very probable one.

But there is an alternative, a way to ensure that kids learn about the proper risks of the world but still have fun. It’s a parent’s nightmare and a kid’s dream, and it’s called an adventure playground.

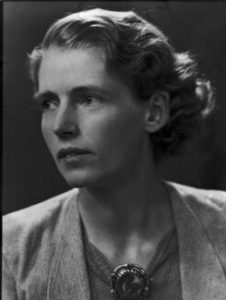

During World War II, a British landscape architect and child welfare activist named Marjory Allen brought a controversial idea from Denmark to the streets of London. She began converting old, bombed out buildings and yards into play spaces for kids. She cleaned them, filled them with loose materials and tools and allowed children to build and create at will. The results were extraordinary.

During World War II, a British landscape architect and child welfare activist named Marjory Allen brought a controversial idea from Denmark to the streets of London. She began converting old, bombed out buildings and yards into play spaces for kids. She cleaned them, filled them with loose materials and tools and allowed children to build and create at will. The results were extraordinary.

“When they [children] set their heart on doing something which may be beyond their capabilities, they’ll stay at it and stick at it until they’ve achieved it, and this builds up a tremendous amount of self-confidence.”

— Marjory Allen

An “Adventure Playground” as she later named it, consisted of several main elements. First and most importantly, loose parts (wood, crates barrels) and tools (screwdrivers, hammers, nails) that are easy to manipulate and create with. Secondly, the space must be separate from main spaces, so children will feel in their own world away from adults and oversight. Lastly, elements of danger in the form of height, speed and rough play must be present.

She observed that when presented with these elements, children respond in a more cautious manner, and learn about the consequences of their actions. Additionally, children respond extremely well to be treated like adults, and play is no exception. This trend soon caught on and spread around the world, landing itself in American, Japanese and European cities.

There are some downfalls of course. Primarily, Adventure Playgrounds are ugly. The loose items and dirt aren’t appealing to the eye of most adults, and don’t necessarily evoke a sense of sanitation. They also require staffing to help restock supplies and ensure the smoothness of how the playground runs. And, of course, there is always a possibility of injury.

However, these limitations are less than the benefits of risky play. Several studies have confirmed that such activity cultivates the proper risk assessment qualities, and should be seriously considered.

So, as you look to make the right choice as to how to let your kids play, don’t forget about the long term effects it has. An adventure playground isn’t exactly necessary, but don’t settle for the bubble wrapped play that has grown in recent years. Let bruises be bruises be bruises, and let the kids play like kids.

![Presidential Rizz [RANKED]](https://amhsnewspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/jfk-600x338.jpg)