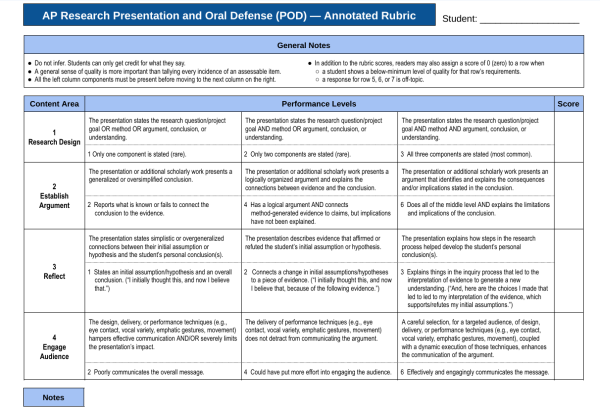

Charleston Hospital Workers Strike of 1969

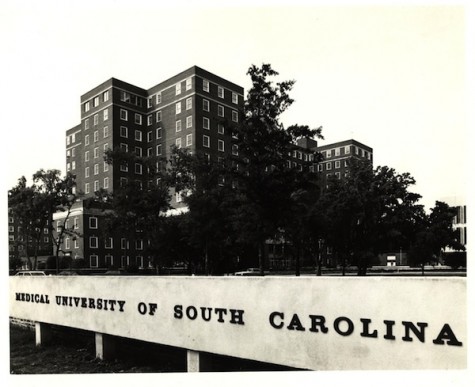

Living in Charleston, most people are familiar with the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), but few people know about the historic events that occurred involving this facility in 1969 during the Civil Rights Movement. Started by a group of African American hospital employees, the strike began as an attempt to convey their grievances to the president of the hospital at the time, William McCord. However, McCord refused to listen to their concerns, so the group occupied his office to which he responded by calling the police. After firing twelve employees for abandoning their posts, McCord would soon have bigger issues.

Led by activist and nurse Mary Moultrie, one of the twelve people fired, the strike campaigned for equal treatment of the African American employees at this hospital. The strike officially started on April 25, 1969, and would go on to last for 113 days, bringing the city of Charleston practically to a halt. Racial discrimination such as keeping the employees in jobs as nurses aides or housekeepers and the constant name calling, using slurs like “monkey grunts”, proved to be fair ground for the strike to continue and bring even Coretta Scott King to the front lines of this event.

To account for the list of grievances, Mary Moultrie and her group wanted to join the New York based Local 1199 medical union to unify against the discrimination faced in this Charleston hospital. With help from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Local 1199 wanted a Civil Rights victory in Charleston that started with creating very necessary unions for low paid workers in Charleston. With opposition from the hospital president, William McCord, those most personally affected pushed further for the unionization. McCord’s comment that he would, “not about to turn a 25 million dollar complex over to a bunch of people who don’t have a grammar school education,” demonstrates the deep rooted discrimination that the African American workers faced at this hospital.

Even a week after the start of the strike, over sixty other African American employees at the hospital joined the efforts. As a result of the strike, South Carolina governor Robert McNair called the situation to be a state of emergency in Charleston, and subsequently ordered a thousand law enforcement personnel to quell the situation. To further oppose the strike, someone fire bombed a union organizer’s home, and arson erupted throughout the area. Strike leader Mary Moultrie even left her home for fear of her safety due to the harsh opposition of their movement.

These events inspired Coretta Scott King, widow to the late Martin Luther King Jr., and other members of the King family to pay a visit to Charleston to support the cause. A mass rally at the Emmanuel AME Church downtown garnered further support by addressing the issues that the original strikers had at their jobs at the hospital in a speech by Coretta Scott King herself.

Eventually, although the strike did not obtain the membership to the union that they desired, they raised the awareness necessary to combat the discriminatory practices at the hospital. With threats to retain hospital training grants, the strike successfully obtained a settlement with the hospital. The hospital rehired all the fired workers, and followed a “six-step grievance process” while promising pay raises. Overall, the strike brought much needed attention to unsatisfactory work conditions and racial discrimination in the workplace.

MUSC in 1971; Waring Historical Library

Walter Reuther, Mary Moultrie, and Ralph Abernathy; Avery Research Center

(http://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/charleston_hospital_workers_mo/grassroots_organizing)