The Pyramid Scheme

Debunking The Fraudulent American Food Pyramid

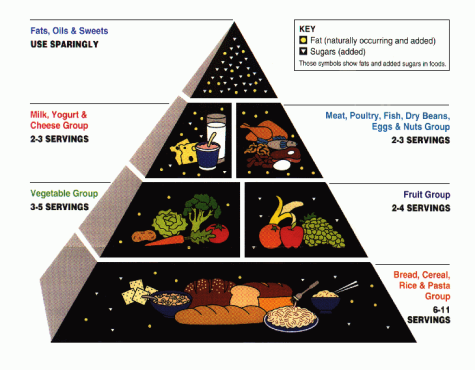

Grains, Vegetables/Fruits, Protein/Dairy, and Fat/Sugar. Taught throughout our primary schooling, the American Food Pyramid has been a model of nutrition since 1992.

A Brief History of the USDA Food Pyramid

The original American Food Pyramid, despite a scheduled release for 1991, was delayed until 1992, with the USDA stating it required more research before official publication. Following its release, it quickly cemented itself as the gold standard for dietary direction among many Americans. Looking back, nutritionists and health professionals agree that the original guidance had several major problems spanning the entirety of the pyramid; the serving recommendation for grains (the bottom of the pyramid and the largest portion) was far too high; the serving recommendations for fruits and vegetables, despite being the second largest level on the pyramid, were far too small; the recommendations for meat and dairy were too high, despite their place relatively high on the pyramid. After 13 years, the original pyramid was discarded for the ‘new and improved’ MyPyramid, which we personally remember from our elementary schools:

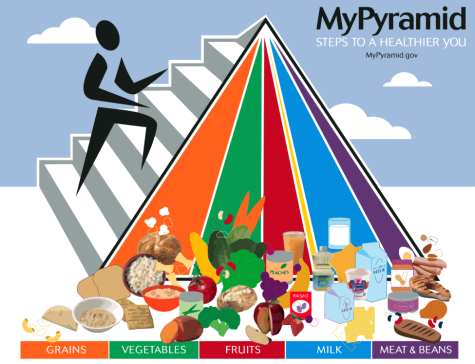

This reiteration of the pyramid is, from a health perspective, a disaster. Grains still take up the largest portion of the pyramid. The Vegetable portion was made larger, but so too was the recommendation for “Milk.” The Milk portion, depicted with all forms of dairy, took the second-largest portion on the pyramid, a horrible direction for the public’s dietary health. Additionally, the suggestions made by the pyramid are far too obscure, with no direct serving sizes. The vertical division of the pyramid adds to this confusion, making it even more difficult to decipher the directions.

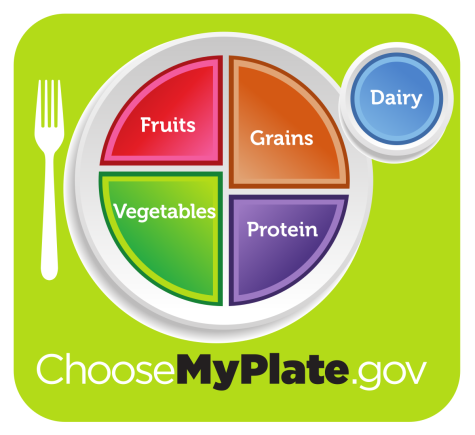

After another 6 years, the pyramid evolved once more into 2011’s “MyPlate,” a graphic you may recognize from our own school cafeteria:

While this alternative features several improvements over the original, the diet it suggests is lackluster at best and debilitating at worst. The recommendation for vegetables now make up the largest portion of the meal, a direction agreed upon almost unanimously by nutritionists, and the size of grains takes a hit as a result, another positive. The servings are somewhat easier to understand, dividing a plate to indicate the recommended intake per meal. However, the dairy recommendation has stayed relatively the same as that of the original pyramid, and arguably its most important problem is shared with its two predecessors: no distinctions are made between heavily processed and natural or organic foods. This issue is most prevalent for protein and grain, where, despite the semi-acceptable serving sizes, the unacceptable generalizations cause major problems. Based solely on the information provided by the MyPlate graphic, considering the serving size of “Protein,” it is not only acceptable but healthy to eat a ½ pound burger every day.

French fries are equal to green beans, and refined grains like crackers and chips are tolerable alternatives to quinoa or brown rice. In light of the absurdity of these guidelines, it is obvious that the eating recommendations pushed by the USDA have colossal problems, as the positive suggestions made by the chart are entirely voided by its lack of specificity.

The Problem

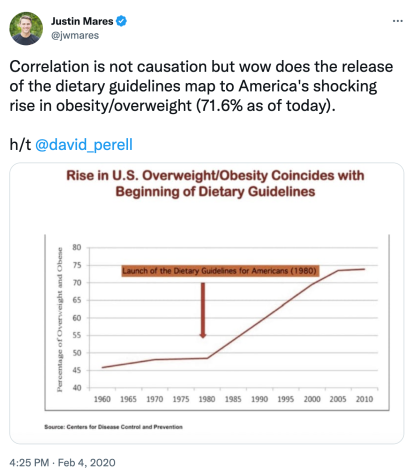

A vast majority of US citizens (40% of consumers use the Food Pyramid to guide purchases, according to a WSJ poll) are confused by the USDA Food Pyramid and have trouble implementing the recommendations in the guide, citing that nearly 1 in 3 adults (30.7%) are overweight, and more than 2 in 5 adults (42.4%) have obesity or severe obesity (statistics drawn from the NIDDK).

A vast majority of US citizens (40% of consumers use the Food Pyramid to guide purchases, according to a WSJ poll) are confused by the USDA Food Pyramid and have trouble implementing the recommendations in the guide, citing that nearly 1 in 3 adults (30.7%) are overweight, and more than 2 in 5 adults (42.4%) have obesity or severe obesity (statistics drawn from the NIDDK).

But what if many Americans do follow the Food Pyramid correctly— and that’s why they end up overweight?

Let us introduce you to Dr. Luise Light: With an MS, EdD, and title of former USDA Director of Dietary Guidance and Nutrition Education Research, Dr. Light was responsible for the original Food Guide Pyramid and revamping USDA’s nutrition information. Hired as an expert to develop new nutrition and cancer prevention programs, she devised the National Cancer Institute’s first diet and cancer prevention guidelines, and directed national health promotion programs with supermarkets, the American Cancer Society, the Red Cross, schools, and State health departments. After the Cancer Institute, she founded and led a “Washington-based nonprofit organization that educated the media, Congress, and the public about cutting edge, controversial health and nutrition issues that were the subject of high profile, disinformation campaigns by industry interests.”

In the early 1980s, Dr. Light was the leader of a group of top-level nutritionists with the USDA who developed the eating guide that later became known as the Food Guide Pyramid. Dr. Light states that after “carefully reviewing the research on nutrient recommendations, disease prevention, documented dietary shortfalls and major health problems of the population,” her team created and eventually submitted the final version of the new Food Guide to the Secretary of Agriculture. However, this version of the Food Pyramid (1991) was never released. Instead, the USDA announced that the Pyramid required more research, and submitted an updated version less than a year later. Dr. Light and her group of nutritionists “were shocked to find that it was vastly different from the one [they] had developed.”

Why?

One word.

Lobbying.

The wholesale changes made to the original Food Pyramid by the Office of the Secretary of Agriculture were calculated to win the acceptance of the food industry. While there is an inherent conflict of interest in the Department of Agriculture’s dual mandates to (1.) promote U.S. agricultural products and (2.) advise the public about healthy food choices, the prioritization of private industry profits over the general health of the population is morally corrupt.

For the US government, the Pyramid is primarily a marketing tool to fuel growth in consumer food expenditures and demand for major food commodities: primarily meat, dairy, eggs, and wheat.

Federal Food Industry Lobbying

Food industry lobbying, and in this article lobbyist influence over the USDA Food Pyramid, is much more than just a conspiracy.

Lobbying includes any legal attempt by individuals or groups to influence government policy or action; this definition specifically excludes bribery. About 8,000 individuals currently register as lobbyists. Among them, an estimated 5 percent represent food companies.

The relationship between food lobbies, the USDA, and Congress has long been a source of concern. Prior to the 1970s, food producers, USDA officials, members of the House, and members of the Senate Agriculture Committees were so interconnected that they were said to constitute an “agricultural establishment,” created to guarantee that federal policies would support the interests of food producers.

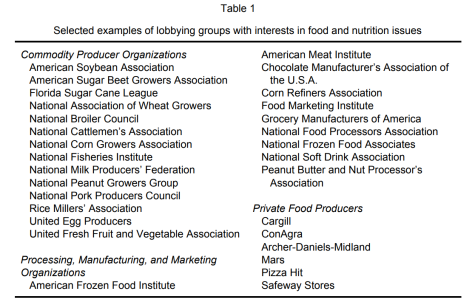

Molecular biologist and nutrition scholar Marion Nestle, the Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health Emerita at New York University, writes in the International Journal of Health Services, Volume 23, that “food lobbies include a multiplicity of groups, businesses, and individuals attempting to influence federal decisions.” Table 1, pictured below, provides a partial list of the most influential groups in this category. The power of food producers and commodity associations is illustrated by how they are much better funded than advocacy groups (with over 20.4 million spent last year alone, according to OpenSecrets). It is important to note that food lobbies are not equal in influence, with beef and dairy lobbies among the most influential. These two specific categories are well funded and distributed among a great many states, each with its own representative in the House and Senate.

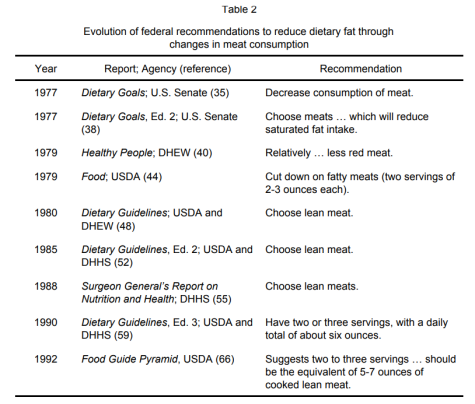

The meat industry was one of the first groups to lobby the USDA, as they took a severe hit in consumption and thus profit in the late 1970s. Marion Nestle summarizes that “foods of animal origin [such as] meat, dairy, and eggs together provide nearly 45 percent of the total fat, 60 percent of the saturated fat, and all of the cholesterol in the U.S. food supply.” Thus, the federal recommendations published in the 1977 Dietary Goals for the United States to consume less fat and cholesterol directly translated into a reduced intake of animal products. By the end of 1977, this message was effectively diffused across consumers, and was reflected by the declining sales of whole milk and eggs. She goes on to note that “as these downward trends continued, and as beef sales also began to decline, food producer lobbies became much more actively involved in attempts to discredit, weaken, or eliminate dietary recommendations that suggested using less of their products.” The report Dietary Goals for the United States was then altered from the original statement “decrease consumption of meat and increase consumption of poultry and fish,” to read “decrease consumption of animal fat, and choose meats, poultry, and fish which will reduce saturated fat intake.” Table 2 illustrates these changes in federal recommendations to reduce dietary fat through changes in meat consumption, evolving from “decrease consumption of meat” to suggesting “5-7 ounces of cooked lean meat” per day— equivalent to eating a half pound burger every day.

Dr. Light further supports this argument by noting a more recent assault on dietary logic: in the 1992 USDA Food Pyramid, changes were made to the wording of the dietary guidelines from “eat less” to “avoid too much,” giving a nod to the processed-food industry interests by not limiting highly profitable junk foods that might affect the profits of these producers.

It is evident that the effects of the revised 1992 Pyramid have been severely in favor of grain, meat, dairy, and walnut industry profit. Matt Hall, spokesman for the baking division of Sara Lee Corporation in Chicago, admits that the six to eleven recommended servings of bread, cereal, rice, or pasta in the 1992 Pyramid, a major jump from the recommended four bread-group servings in the 1950s, helped fuel double-digit growth for some bread products through the late 1990s. He goes on to blatantly state the following:

Originally, Dr. Light’s nutritionist group had placed baked goods made with white flour, including crackers, sweets and other low-nutrient foods laden with sugars and fats, at the peak of the Pyramid. In the 1992 publication of the remodeled Pyramid, the food products in this layer were now carried over to the base of the Pyramid, under “grains”— the direct opposite of where they were ranked before.

Eric Hentges, executive director of the USDA’s Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (the group responsible for the pyramid overhaul), has met with “more than a dozen industry groups,” according to a copy of his calendar. Among these groups are the U.S. Potato Board, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, the Chocolate Manufacturers Association, and the California Walnut Commission. Groups that were not represented in these lobbying organizations are fruit and vegetable producers. Consequently, the overabundant nutrition recommendations of grain, protein, and fat/sugar groups stem directly from the private lobbying efforts of the food industry.

Nut farming/producer groups, such as the California Walnut Commission mentioned above, have played a shockingly large role in this lobbying effort. In a series of 254 letters from citizens, companies, and other groups to the US Department of Agriculture in 2004, “walnut growers were the most prolific,” with more than 20 of the letters touting the nut’s alpha-linolenic acid, advertised as an essential fatty acid that cannot be manufactured by the body.

The dairy industry is also overly involved in lobbying the USDA and Food Pyramid. The National Dairy Council continuously argues for a lift in the daily recommendation of dairy products, from the current two or three servings to an increased three or four. Alternatively, the Harvard Eating Plate (a healthier substitute for the USDA Food Pyramid, to be discussed later) recommends limiting milk and dairy products to “one to two servings per day.” This differs greatly from the Food Pyramid’s recommendations, which has been lobbied into overpromoting milk and dairy products. In addition to accusations about the actual design of the milk category on the Pyramid, with an overly vibrant light-blue insinuating a nutritional superiority in contrast to other categories, MyPlate and USDA Food Pyramid’s creation of milk as an individual group implies that it is an essential part of a healthy diet. Not only does the overgeneralization of “dairy” equate 1.5 cups of ice cream to a glass of low-fat milk, the connotation of milk as an essential category of healthy nutrition goes against a great portion of the population who are lactose intolerant or choose to abstain from dairy, as well as a number of cultures that have historically consumed little to no dairy products. Moreover, the dairy industry excessively puts down the idea that the Food Pyramid is at fault for mass malnutrition and the obesity epidemic. The Oregon Dairy Council states that “we argue instead that it [the Food Pyramid] has become the unfortunate scapegoat for a society that has lost all focus when it comes to balance, variety and proportionality,” a hypocritically ignorant attempt of support towards the sell-out of a government health organization.

While it is important to take into account the plethora of evidence that positively supports the assertion that private industry lobbying influences nutrition research and publication, it should be noted that some research offers an alternate perspective. According to research done through Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and the City University of New York, the analysis of this evidence is often biased and faulty, and they believe that “it is an error to demonize, almost as a reflex, scientists, and their research when there is evidence of private funding … conspiratorial narratives in science can distort the past in the service of contemporary causes and obscure genuine uncertainty that surrounds aspects of research, impairing efforts to formulate good evidence-informed policies.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Light concludes that the USDA has had a “long and cozy relationship with the food industry, whose executives often end up in USDA leadership positions (for instance, Mr. Hentges, formerly of the National Pork Producers’ Council).” Consumer groups have unsuccessfully requested that 7 of the 13 panel members who were writing the Food Guidelines be removed because of their close ties to the food industry. She closes by emphasizing a shocking statistic:

Despite the overabundance of evidence that lobbying has directly and detrimentally influenced US Federal Health Organizations, and with it the nutritional health of the US population, Marion Nestle emphasizes that “lobbying activists are entirely legal and available to consumer groups as well as to food producers. It should be clear, however, that the playing field is not level; food producers possess far greater resources for lobbying activities than do consumers.” She goes on to cite a commentator, who believes that it is unfortunate that “good advice about nutrition conflicts with the interests of many big industries, each of which has more lobbying power than all the public interest groups combined.”

However, the fact that food lobbies employ legal methods to promote their goals is not sufficient enough to justify their use of power based on economic and political influence rather than the morality of the common good. The controversy over the Food Guide Pyramid demonstrates that the connections between members of Congress, USDA officials, and food lobbies must “continue to raise questions about the ability of federal officials to make independent policy decisions,” Marion Nestle concludes.

Private Lobbying

While the effects of political lobbying across the food industry are apparent, private lobbying is often even more disastrous for conditioning public thought, by influencing private research to publish false or misleading results. Several prime examples of this stem from the sugar industry. A research report released by the University of California San Francisco reviewed 15 years of studies about whether soda consumption can lead to obesity and diabetes. Of the 60 studies they examined, 34 were conducted by independent scientists. All 34 of the studies conducted by independent scientists showed a clear link between drinking soda and developing obesity or diabetes. However, of the 26 studies done by scientists with financial ties to the beverage industry, none discovered a link between sugary soft drinks and poor health.

The extent of private lobbying by the sugar industry does not stop there. In the 1950s, disproportionately high rates of coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality in American Men led to studies of the role of dietary factors increasing the risk of CHD. Cholesterol, phytosterols, excessive calories, amino acids, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals were among those studied. The two primary groups identified were (1.) sugar, and (2.) total fat, saturated fat, and dietary cholesterol. Over the next two decades, opinions supporting the role of added sugars in CHD risk grew less common, until eventually the first publication of Dietary Guidelines for Americans entirely focused on reducing total fat, saturated fat, and dietary cholesterol for CHD prevention.

Where did this sudden decrease in attention to sugar in CHD risk come from?

There was a strategic profit opportunity for the sugar industry: increase sugar’s market share by getting Americans to eat a lower-fat diet. This opportunity was directly addressed in a 1954 speech by the Sugar Research Foundation’s president: If the population could be persuaded to eat a lower-fat diet, they would need to replace that fat with something else. Therefore, America’s per capita sugar consumption could go up by a third, given the carbohydrate industries were to recapture this 20 percent of the calories in the US diet (the difference between the 40 percent which fat should hold and the 20 percent it was decreased to) and sugar maintained its present share of the carbohydrate market.

The sugar industry achieved these goals with a sum of about $5.3 million dollars, according to a publication by JAMA Internal Medicine. The Sugar Research Foundation would pay nearly $50,000 in today’s dollars for “a review article of the several papers which find some special metabolic peril in sucrose and, in particular, fructose.” The association paid a similar sum to 3 Harvard nutrition professors to publish a research review that would refute evidence linking sugars to CHD.

Further evidence suggests that the Harvard studies were in fact influenced by this bribe. One of their studies, concluding there was a health benefit when people ate less sugar and more vegetables, was dismissed because that “dietary change was not feasible.” Another study, in which rats were given a diet low in fat and high in sugar, was rejected because “such diets are rarely consumed by man.” In a hypocritical contrast, The Harvard researchers then turned to studies that examined risks of fat— conducting epidemiological research nearly identical to the studies on sugar that were ultimately dismissed.

Co-author of this JAMA Internal Medicine study uncovering the sugar industry lobbies, Stanton Glantz, inferred that “It was a very smart thing the sugar industry did, because review papers, especially if you get them published in a very prominent journal, tend to shape the overall scientific discussion.” This assertion is accurate based on the findings of this paper, as lobbies to the government rarely lie uncovered, while the private bribes made by the sugar industry have ultimately produced false facts, conditioning an entire nation to believe that saturated fat and dietary cholesterol are nutritional dangers (to be expanded on later).

Unfortunately, this type of private lobbying is very common. Marion Nestle spent a year informally tracking industry-funded studies on food, and found that “roughly 90% of nearly 170 studies favored the sponsor’s interest.” For instance, studies funded by Welch Foods (the producer of Welch’s 100% Grape Juice) found that “drinking Concord grape juice daily may boost brain function.” In a more severe example, Coca-Cola has funded high-profile scientists and organizations, such as the new nonprofit organization called the Global Energy Balance Network, to promote their argument: Weight-conscious Americans are overly fixated on how much they eat and drink while not paying enough attention to exercise. Health experts say this message is “misleading and part of an effort by Coke to deflect criticism about the role sugary drinks have played in the spread of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.” The goal of Coca-Cola’s message is to persuade consumers that physical activity can offset a bad diet, such as the one incited by drinking soft drinks every day, despite evidence that “exercise has only minimal impact on weight compared with what people consume.” In the aftermath of this investigation, Coca-Cola released details on its private funding, stating that it granted $132.8 million toward scientific research and partnerships.

What now?

For starters, it’s what works for you. If the current version of MyPlate has helped you reach your dietary goals, stick to what works. However, a much healthier alternative is offered under the Harvard Healthy Eating Plate, which corrects the nutritional misconceptions mentioned throughout the article— suggesting to limit dairy to 1-2 servings a day, for example. Instead of an unclear plate with overly vague categories, the guide elaborates on the importance of differentiating nutritious value of products beneath the same food group, such as avoiding refined grains like white rice and white bread.

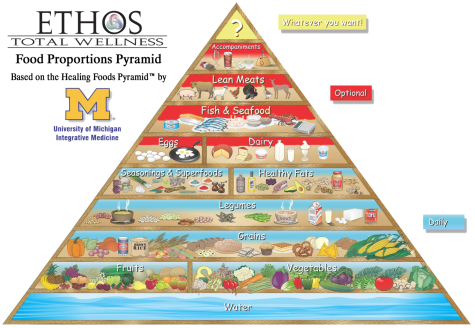

Another healthy alternative to the USDA food Pyramid, one that we prefer over the Harvard Healthy Eating Plate, is the Food Proportions Pyramid by the University of Michigan department of Integrative Medicine.

Apart from highlighting variety in color, flavor, and portions across consumer diets, the University of Michigan Food Pyramid Fat Guide partially mends the discrepancies produced by the sugar industry. Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) are labeled as healthy, while Saturated Fats and Trans-Fats are recommended to be limited. While PUFAs like omega-3’s are undoubtedly beneficial to human nutrition, the outlook on saturated fats still reflects the decades of bias against fat as a food group.

Apart from highlighting variety in color, flavor, and portions across consumer diets, the University of Michigan Food Pyramid Fat Guide partially mends the discrepancies produced by the sugar industry. Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) are labeled as healthy, while Saturated Fats and Trans-Fats are recommended to be limited. While PUFAs like omega-3’s are undoubtedly beneficial to human nutrition, the outlook on saturated fats still reflects the decades of bias against fat as a food group.

Branching off of their Food Pyramid, University of Michigan’s Fat Guide states that “saturated fat eaten in excessive amounts is the main culprit in raising total and LDL (‘bad’) cholesterol, which can increase risk of heart disease.” Blanket statements like these are misleading, especially when certain categories of fats are simply and directly labeled as “bad,” as the guide quotes. Evidence is mounting that not only are all but non-naturally occurring fats (such as trans fatty acids) beneficial to dietary health, but also that “a low-fat diet and/or a diet high in only polyunsaturated fatty acids may be detrimental to one’s health.” It is the quantity of these fats consumed that raises health risks across a nation plagued with obesity.

There is currently a wide body of knowledge in support of saturated fats, citing them as nutritious, beneficial, and most notably “heart protective.” Shorter-chained saturated fats have been used by physicians as conjunctive treatment in liver disease. They are directly absorbed into the bloodstream and utilized by the liver, with their short chain length allowing them to be directly converted into energy. This reduced metabolic load allows the liver to “optimize its function of detoxifying, producing bile, and maintaining optimal blood sugar levels.”

The effects of saturated fats in pregnancy are also apparent. In one study, it is suggested that a maternal diet high in unsaturated fatty acids can potentially cause breathing problems for the newborn. In another study, “pregnant mice were fed saturated fat in the form of coconut oil, as opposed to another group of mice fed unsaturated fats. Upon comparison, the pregnant mice fed saturated fats were found to produce offspring with normal brains and higher intelligence.” It is also important to note that the composition of fats in coconut oil is similar to the fats found in maternal human milk.

Coconut oil has been shown to be antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiprotozoal. The saturated fats in coconut oil, such as capric acid and lauric acid, have been found to boost the immune system. Lauric acid has been shown to reduce viral load in HIV patients.

In fact, in his publication Concerning the Possibility of a Nut…, Anderson Castelli found that there is “no relation between saturated fat intake and risk of CHD was observed in the most informative prospective study to date,” and even goes on to assert that “we found that the people who ate the most cholesterol, ate the most saturated fat, ate the most calories, weighed the least, and were the most physically active.”

Overall, with healthy portions, saturated fats can be used to “boost the immune system, for weight management, as antimicrobials, to support the structure of gut mucosa, and as dietary adjuncts in cases of chronic degenerative disease, such as cardiovascular disease, liver disease and cancer.”

Connecting back to the history of lobbying, Mary G. Enig (Ph.D.) writes about the US dietary agenda’s devastating effect on the coconut industry: “It is important to realize that at that time (1960s) the edible oil industry in the United States seized the opportunity to promote its polyunsaturates. The industry did this by developing a health issue focusing on Key’s anti-saturated fat bias. With the help of the edible oil industry lobbying in the United States, federal government dietary goals and guidelines were adopted incorporating this mistaken idea that consumption of saturated fat was causing heart disease.”

With this large quantity of evidence, alongside the underlying knowledge that many common assumptions about nutrition have either been lobbied or rooted in bribed research, we can go on to understand that one of the most viable solutions to a food guide is to conduct personal research, grounding a nutritious diet in your own findings and modeling it for what you need. In our own studies, for instance, we have found that there is a significant health difference between processed red meat and organic, natural, unprocessed meat. Apace with our studies on saturated fat, we have concluded that our above-average meat consumption works for us and is not a major risk for CHD, cancer, or diabetes. However, conducting selective, biased research in order to support your unhealthy eating habits very obviously does not fit under our conclusion.

Final Words

As a general guideline, processed foods are best to be avoided, and whole foods (such as whole grain and fresh fruit/vegetables) are most beneficial. All in all, remember that the USDA’s interest does not lie with your nutritional health; Instead, our US government and aligned health organizations have “sold out” in order to benefit private food industries. With the pages of evidence presented on private industry influence, federal lobbying, and research bribing, we can conclude that the USDA Food Pyramid is not only dangerous to the health of the United States population, but also modeled to reflect the profit interests and increase consumer demands of food industry organizations. Therefore, we recommend that you do not follow the nutritional labels on food products, and instead formulate your own diet based on (1.) what works for you and (2.) conducting personal research.

Seriously, The Final Words This Time (Not Joking)

It is imperative to note that healthy eating does not and should not equate to boring eating. Making smart choices can make eating healthy as enjoyable as eating ice cream, such as eating a wide variety of foods and cooking in different ways. Also, it is not necessary to completely cut out your favorite foods, no matter how unhealthy they may be, as everything is acceptable in moderation.

Actual Final Words (We Were Joking)

Thank you very much for reading, and remember that the USDA does not care about your health due to conflict of interest with promoting private industries and, well, making money. Be sure to delve into your own research, but be weary with studies that are funded by relevant food organizations.

Boris and Ransome, out.

Works (Improperly) Cited

https://blogs.bu.edu/calandra/files/2016/06/FoodLobbiesTheFoodPyramidandU.S.NutritionPolicy.pdf

http://www.whale.to/a/light.html

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB109104875075676781

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Food_pyramid_(nutrition)

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A153098599/AONE?u=nort45678&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=a31539f9

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A113946054/AONE?u=nort45678&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=2173da35

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A115767014/AONE?u=nort45678&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=15c47aa7

https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-eating-plate/#dga2005

https://www.opensecrets.org/industries/lobbying.php?cycle=&ind=N01

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A495033392/AONE?u=nort45678&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=2ebcdc42

http://math.colorado.edu/~walter/MATH2380/Resources/sugar.heart.2016.pdf

https://www.integrativeasheville.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Optimal-Fats-Handout.pdf

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A97994362/AONE?u=nort45678&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=968dc27a

https://thescienceofnutrition.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/concerning-the-possibility-of-a-nut.pdf

Ella Chapman • Jan 27, 2023 at 11:32 am

Very insightful article, made me wary of the US food pyramid

Laura Robertson • Jan 27, 2023 at 11:32 am

This was a fascinating article! I read and loved every word. My favorite part was how you somehow tied lobbying into the food pyramid. Great JOB!