The Issue of Posthumous Music Releases

Whether a fan or not, many people can relate to the shock and grief as multiple hip hop icons were taken from the world in recent years. Musicians and pop culture icons like Pop Smoke, Juice Wrld, Nipsey Hussle, XXXTENTACION, and Mac Miller have seen posthumous album sales rise up to 500% after their unexpected deaths, showing their huge popularity. Although some posthumous albums have done well to commemorate the lives of these artists, some have fallen short, drawing criticism as to whether these albums should have been released in the first place.

Circles by Mac Miller is an example of a perfect posthumous album. The songs were nearly complete and the album was finished tastefully, involving those closest to him. Conversely, many argue that Pop Smoke’s discography was stained by his second posthumous album, Faith. As shown by Pop Smoke’s short and simple snippets from this second posthumous album release, record labels often edit and release incomplete music with no creative input or indications from the artist. Blatantly going against Pop Smoke’s wishes: “I don’t do songs with [people]… my tape ain’t have nobody on it.” The record label did their best to patch the gaping holes in Faith with a huge array of features from many artists Pop Smoke had never collaborated with. Pop sounding features from Dua Lipa and Chris Brown clash with Pop Smoke’s signature sound and persona, and highlight the true purpose of the release of Faith.

“Woo Baby” with Chris Brown is severely limited by Pop Smoke’s shallow verse. Pop Smoke can only sing, “Lightskin, tatted,” so many times before it becomes boring. With no depth to work off of, Chris Brown did what he is best at, making plain, shallow, and boring verses about the female body. This song’s failure to provide anything of worth to this album is by no means Pop Smoke’s fault, as it lacked any creative direction to begin with. It should have never been released, especially not in a posthumous album.

“Demeanor” with Dua Lipa contrasts “Woo Baby,: yet contains no substantial value to the album. The bubbly pop sounding beat feels artificial and forced, confusing fans who looked for this album in their grief over Pop Smoke’s death. With no offense to her as an artist, Dua Lipa truly does not belong on a Pop Smoke album. Pop Smoke’s harsh masculinity, with many lyrics about drugs, guns, and sexualization of women does not mix well with Dua Lipa’s female empowerment voice. It is obvious that the producers of Faith brought on Dua Lipa to attract a female audience, in a feeble attempt to make more money off of Pop Smoke’s name.

It is no surprise that the only good songs on the album were the songs that involved fellow Brooklyn drill rappers. In songs like 30 with Bizzy Banks, Banks’ featured verse matched Pop Smoke’s energy in every way, and supported Pop’s decently long verse. It is most important to note that while these songs were good, they did not commemorate Pop Smoke’s life nor provide any comfort to those grieving his death. Shouldn’t posthumous albums be sad, or at least reflective?

This same story has been repeated many times throughout history. Loyal to the Game by Tupac flipped his signature dark west-coast funk sound on its head with more guest stars and overproduction from Eminem, who was assigned to produce the album. Albums like The King and I, a 2017 collab album with The Notorious B.I.G. and his wife, and Kurt Cobain’s Montage of Heck: The Home Recordings, a collection of personal recordings that seem like a violation of Cobain’s privacy, should have never been released to the public. They are an exploitation of the artists’ image and sound that were made to make as much money as possible. Yet if albums like these have been released for decades, why hasn’t anyone done anything to stop it?

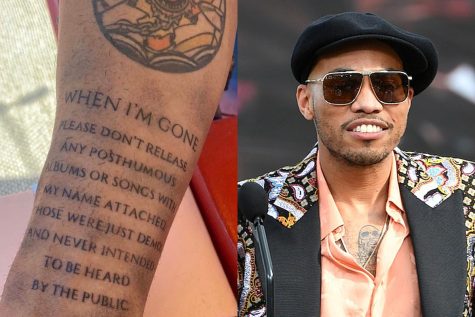

The issue is complicated because all the music of deceased artists’ belongs to their heirs. Although most heirs have good intentions, they may not be very connected to their relative’s music and most importantly, are offered large sums of money in exchange for their permission to release the music. While fans can boycott exploitative labels to limit their power, a long term solution is needed. The introduction of music wills, for artists to instruct heirs on how to manage their music after their death, would effectively limit the influence of labels. A powerful, yet more figurative example of a music will, is Anderson Paak’s tattoo, saying, “Please don’t release any posthumous albums or songs with my name attached…”

This is not only an insurance for his name and brand, but also criticizes past releases of posthumous albums from artists who may not have been as prepared. Powerful messages like these bring attention to the issue of posthumous releases, which are only getting more prevalent. More and more artists are dying at young ages from larger issues like drug abuse and violence, leaving these young artists vulnerable to the overarching power of record labels. Without any monumental changes, more of these artists will pass away in the future and I hope to see their legacies protected.