Black History Month In Charleston

February 17, 2017

A few days ago in AP Literature, my class read a poem titled “One River, One Boat” by Marjory Wentworth. According to Mrs. Bortz, the poem was written for Nikki Haley’s gubernatorial inauguration but Wentworth’s piece was not read at the event and now instead serves a different purpose. “One River, One Boat” highlights the unique atmosphere surrounding Charleston regarding history, race, and modernization. Below is the poem:

One River, One Boat by Marjory Wentworth

Because our history is a knot

we try to unravel, while others

try to tighten it, we tire easily

and fray the cords that bind us.

The cord is a slow moving river,

spiraling across the land

in a succession of S’s,

splintering near the sea.

Picture us all, crowded onto a boat

at the last bend in the river:

watch children stepping off the school bus,

parents late for work, grandparents

fishing for favorite memories,

teachers tapping their desks

with red pens, firemen suiting up

to save us, nurses making rounds,

baristas grinding coffee beans,

dockworkers unloading apartment size

containers of computers and toys

from factories across the sea.

Every morning a different veteran

stands at the base of the bridge

holding a cardboard sign

with misspelled words and an empty cup.

In fields at daybreak, rows of migrant

farm workers standing on ladders, break open

iced peach blossoms; their breath rising

and resting above the frozen fields like clouds.

A jonboat drifts down the river.

Inside, a small boy lies on his back;

hand laced behind his head, he watches

stars fade from the sky and dreams.

Consider the prophet John, calling us

from the edge of the wilderness to name

the harm that has been done, to make it

plain, and enter the river and rise.

It is not about asking for forgiveness.

It is not about bowing our heads in shame;

because it all begins and ends here:

while workers unearth trenches

at Gadsden’s Wharf, where 100,000

Africans were imprisoned within brick walls

awaiting auction, death, or worse.

Where the dead were thrown into the water,

and the river clogged with corpses

has kept centuries of silence.

It is time to gather at the water’s edge,

and toss wreaths into this watery grave.

And it is time to praise the judge

who cleared George Stinney’s name,

seventy years after the fact,

we honor him; we pray.

Here, where the Confederate flag still flies

beside the Statehouse, haunted by our past,

conflicted about the future; at the heart

of it, we are at war with ourselves

huddled together on this boat

handed down to us – stuck

at the last bend of a wide river

splintering near the sea.

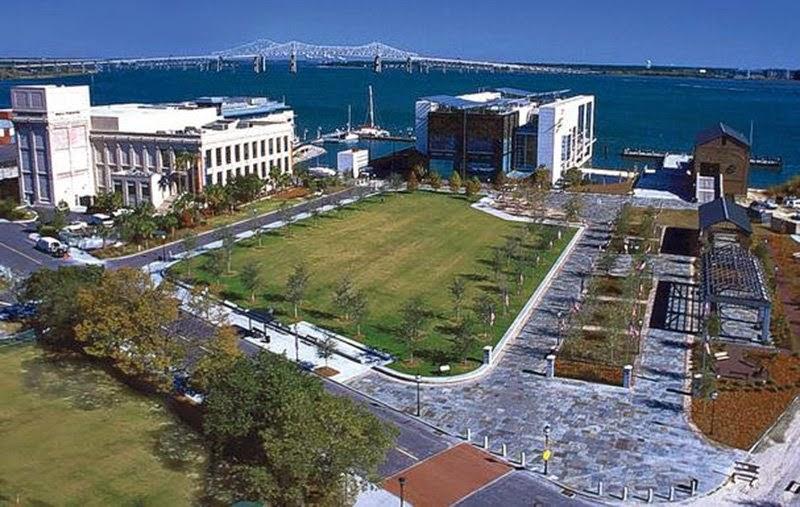

Before my class read the poem, Mrs. Bortz explained some important allusions and images found within it. First, Gadsden’s Wharf, situated on the Charleston Harbor and now home to the South Carolina Aquarium and Liberty Square, served as the largest American port in the slave trade after transporting nearly 40% of all African slaves into the United States according to the economist.com. Wentworth mentions how “the dead were thrown into the water,” polluting the Cooper River with bodies.

As a longtime citizen of Charleston I could not believe what I read in Wentworth’s poem. I knew that centuries ago slaves had been sold in in this city in the Market and had worked on plantations such as Boone Hall. What I had not realized was the severity and torture of these people that had happened in the past of my hometown; I can’t count the number of times I had stood on the overhang of the Aquarium looking out over Charleston Harbor without knowing the history of the Wharf or the number of Africans that had been killed and thrown into the seemingly calm Harbor below.

Wentworth requests that the Charleston community “toss wreaths into this watery graves;” it is imperative that as a society Charleston recognizes the past so that race relations can continue to improve. Recently, Charleston was shocked when a white supremacist brutally murdered 9 African-American members of Mother Emmanuel Church. Immediately after the massacre, the community banded together in support of the Church and now the city is stronger than ever.

This February, I urge you to consider the weight and meaning of Black History Month. Remember the suffering, sacrifices, and successes African Americans have had in the past and ensure that society continues moving towards an inclusive, better future.