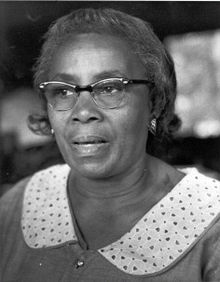

Septima Poinsette Clark

Leading the way in not only Charleston’s own Civil Rights Movement, but the nationwide Civil Rights Movement, Septima P. Clark helped to advance equality of education throughout the country, revolutionizing the way that teachers were treated. Referred to by Martin Luther King, Jr. as “The Mother of the Movement,” Clark was born on May 3, 1898 on Johns Island. The daughter of a former slave, her father Peter Poinsette, she was raised in a strict household under the firm leadership of her mother Victoria Warren Anderson Poinsette. Learning to read and write under the instruction of an elderly woman who lived across the street, Clark eventually attended Avery High School in Charleston, graduating to become a teacher on Johns Island at the age of eighteen. In 1942, Clark would go on to receive her B.A. at Benedict College in Columbia. While teaching on Johns Island, Clark experienced her initial involvement with the Civil Rights Movement.

As the principal of her school, Clark made only $35 a week, while the teacher teaching at the white school across the street made $85 a week. It was this discrepancy in pay that led Clark to begin pushing for the equalization of teacher salaries. After moving to teach at a private academy in the heart of Charleston, Clark began working with the NAACP, gathering signatures on a petition that would push to allow black principals at Avery, the academy at which Clark taught. In 1920, due in large part to Clark’s work, black teachers could officially become principals in Charleston County public schools and by 1945 Clark, along with Thurgood Marshall, won a case about equal pay for white and black teachers in Columbia. However, when Clark became vice-president of the Charleston NAACP branch, the South Carolina legislature passed a law that banned city and state employees from being involved in civil rights organizations, forcing her to choose between her job as teacher and her involvement with the NAACP. Clark refused to leave the NAACP and was thus fired by the Charleston City School Board.

Not one to remain idle, Clark promptly obtained a job as the full-time director of workshops at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee. There she taught a wide range of literacy courses, with the goal of transforming uneducated black citizens into potential voters. Under Clark, programs expanded until she was eventually teaching courses focusing on such subjects as filling out driver’s license exams, voter registration forms, Sears mail-order forms and checks; garnering wide spread participation Clark even taught Rosa Parks, who would go on to lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott. As the director of Highlander Clark also kickstarted “Citizenship Schools,” a novel idea that pushed to not only increase literacy but also to educate black communities on their citizenship rights and work to get individuals involved in the political movement, and to push for their own voting rights.

Eventually, Clark’s Citizenship Schools grew so large that they were included as a program in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, becoming an essential part of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s movement of nonviolence. Under Clark more than 10,000 teachers were trained to teach at citizenship schools and before 1969 over 700,000 student’s of citizenship schools became registered voters. Due to the success of her citizenship schools, Clark was appointed the SCLC’s director of education and teaching, becoming the first woman to serve on their board. As the director Clark experienced rampant sexism, being questioned arduously for her position on the board and underestimated by men in leadership positions with the SCLC. Clark would go on to say that the unfair treatment on women was “one of the greatest weaknesses of the civil rights movement.”

In her later life Clark went on to serve two terms on the Charleston County School Board, continuing her work in education. She was awarded the Living Legacy Award in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter the Martin Luther King Jr. Award in 1970, and was posthumously awarded the SCLC’s highest award, the Drum Major for Justice Award in 1987. Clark died on December 15, 1987 on Johns Island and was buried at Old Bethel United Methodist Church. Heralded by such black activists and leader as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, Clark revolutionized the field of education as well as emphasizing the importance of education in the civil rights movement, her prosperous life supporting her belief that, “whenever there is chaos, it creates wonderful thinking. I consider chaos a gift.”